India has failed to eliminate TB

We have not been able to meet our self-committed goal of eliminating TB from India by 2025

Introduction

SDG Target 3.3 | Communicable diseases: By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases. That is what the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal Target 3.3 reads. In 2019, 14% of deaths occurred due to communicable diseases. Naturally, UN-SDG 3.3 makes sense, as eliminating avoidable and often treatable epidemics should be eliminated immediately.

In this article, we delve into the urgent and pressing issue of tuberculosis (TB) in India. The slogan TB हारेगा, देश जीतेगा (TB will lose, the country will win) has echoed since our childhood, but many are unaware of the looming deadline: December 31, 2024. The question remains, has India emerged victorious in this battle?

Nope, not at all. TB has won decisively. Just like the Indian test cricket team did with New Zealand in the ongoing series, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has severely underestimated tuberculosis.

It's known as 'The White Death' for a reason!

Failures

The TB incidence rate in 2023 was 199 per lakh people, 199 more than 0. This number is way above the ministry's target of 77 per lakh for 2023. India still needs to reduce TB cases to a low enough level to eradicate it by 2025.

Moreover, the ministry is behind on every metric it aims to meet by 2023. Treatment success, mortality rate, and proportion of notified patients receiving financial support through Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) are some examples of this. However, the most significant deficit between the 2023 target and the actual number is in the proportion of notified TB patients offered Drug-Susceptibility Testing (DST); the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare aimed to offer DST to 98% of TB patients by 2023, but the actual number stands at only 58%.

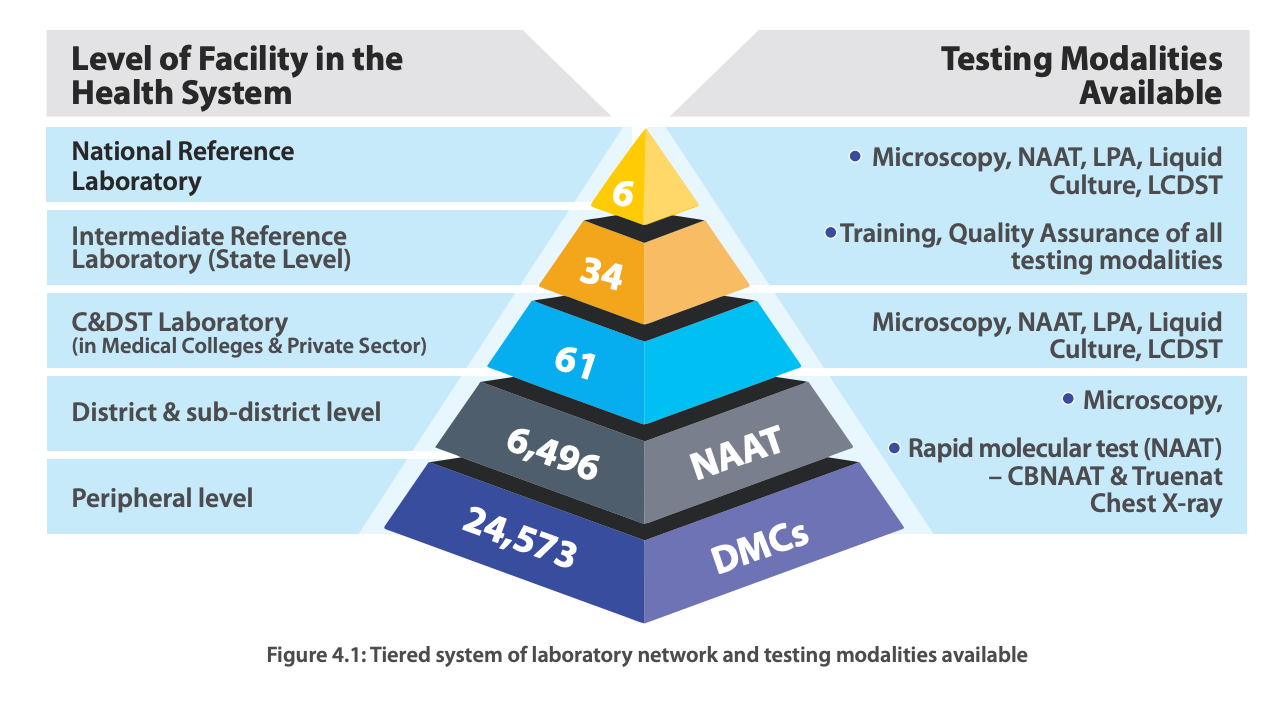

India's need for more testing centres and laboratories is a significant hurdle. Currently, only 61 C&DST laboratories offering Liquid Cultures and LCDST exist in the country. District, sub-district and peripheral health centres are ill-equipped to handle Drug-Resistant TB (DR-TB). The scarcity of LCDST testing centres results in low DST referral numbers and, consequently, a low proportion of DR-TB cases being successfully diagnosed and treated.

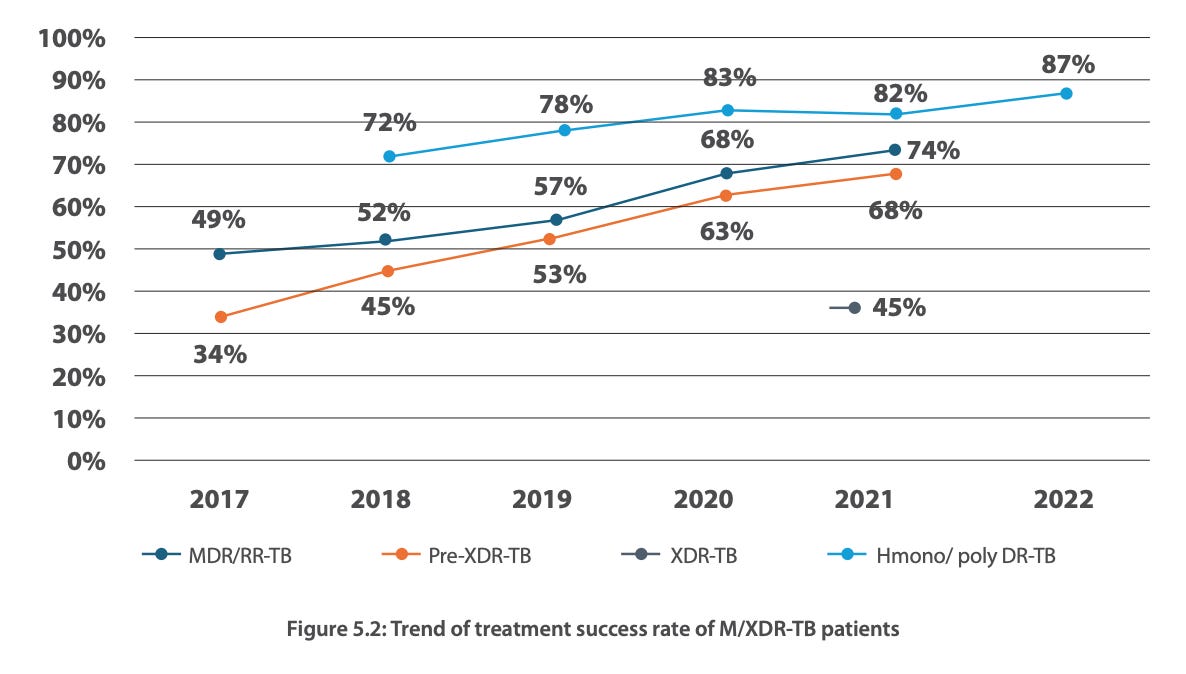

When it comes to DR-TB, our success rates for treatment are alarmingly low. India's success rate for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (RR-TB) is a mere 68%, and for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB), the success rate is a dismal 45%. This reality underscores the urgency of our efforts to bring the TB mortality rate to 0.

Lastly, India does not have health centres in all parts of the country, predominantly tribal areas. As of March 31, 2022, there is a shortage of 11288 Sub Centres, Primary Health Care (PHC) centres, and Community Health Care (CHC) centres in tribal areas. Without adequate health centres in tribal areas, we are a long way from eradicating TB.

The way forward

Naturally, focusing on TB prevention is a key goal for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Establishing peripheral health centres and Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (AAMs) in places with vulnerable populations (rural, tribal, and difficult-to-access areas such as deserts or hills) is the solution. However, this requires a significant amount of funding and administration.

One way the government has tried to solve this issue (and, to some extent, succeeded) is privatisation and community engagement. Over 1,800 NGOs are currently involved in India's Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP). Moreover, more than 1.5 lakh Ni-Akshay Mitras have come forward to assist TB patients as part of the Pradhan Mantri TB Mukt Bharat Abhiyaan that began in September 2022. The government has also introduced financial incentives for Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) and Anganwadi workers if they carry out TB screening and treatment efforts at their respective centres.

If there is one factor India surely doesn't lack, it is enthusiastic and capable people. All the government needs to do is give these people a little nudge, and they will come together and achieve enormous feats. Community engagement is a cheap and effective way of tackling the elimination of TB. With significant efforts, it is very possible that India will meet the UN deadline of eradicating TB by 2030.

Eventually, TB हारेगा, देश जीतेगा.